Summer squashes and green beans always surprise me with how productive they are. I had a total of two yellow straightneck squash plants, one zucchini, and around fifty green bean plants in my garden over a three-month period in 2024. While that may not sound like much at first, those plants produced enough fruit for us to get thoroughly overloaded with summer squash (as always happens—you can only give away so many to the neighbor!) and fill our freezer with squash soup, squash cubes, and bags of green beans that we’re still enjoying well into winter.

Despite the success, I ran into one particularly challenging problem that ended up prematurely terminating my squash crop in July. Because of this unexpected and frustrating setback, I’ve learned so much and have since devised a planting strategy that will, I believe, effectively mitigate the same issue this year. I’ll find out once I test it, but I’m confident it will yield an even more abundant harvest (so I can pester more people with squash). I’m excited to share what I learned with you!

This is part five of the “Everything I Grew” series, where I review the varieties I grew in 2024, share my likes and dislikes, difficulties encountered, lessons learned, and reveal any new varieties that I’m growing in 2025.

Last time I went over all of the pepper varieties I grew; hot, smoky, and sweet.

This time we’ll continue reflecting on the main summer crops—and hopefully absorb some heat through the photos—by looking at the summer squashes and green beans. Up first, the beans.

Green Beans (Phaseolus vulgaris)

Green beans are really a joy to grow. So long as you sow them after the soil has sufficiently warmed (seventy degrees Fahrenheit), they don’t require much maintenance or additional inputs. Once they get going, they pump out a load of beans per plant and will produce at a higher rate if you pick them often. On top of that, they’ll fix atmospheric nitrogen for you and deposit it into your garden soil.

There are two main types: pole and bush beans. Pole beans require trellising and bush beans are, as the name implies, more like a bush. Bush beans can still exhibit pole-like tendencies, occasionally sending out a “runner” that will climb any nearby vertical object. Mostly, though, they produce leaves and flowers close to the ground, reaching around eighteen inches in height.

I prefer growing bush beans because they’re more compact and less complicated. Since they don’t require any trellising, I can grow them anywhere. Beans mature relatively quickly for a summer crop—in roughly fifty days—so, in addition to my main crop of beans, I like to fill gaps in my summer garden with bean plants. Doing so is a lot simpler without having to set up a trellis first. Beans sown in the gaps often produce fruit, but even if they don’t they always improve the soil and act as a “living mulch” without crowding or shading out my other plants.

In 2024, I grew two varieties of bush beans: Provider and Compass.

Provider Bush Bean

Provider is a bean’s bean. It is the green bean everyone thinks of when they think “green bean.” It is an early maturing variety that lives up to its name by very reliably producing heavy sets of beans, even in challenging conditions. Along with a few cherry tomatoes and one zucchini, Provider bush beans were part of my first summer harvest this year.

The variety is open-pollinated and prolific, with nearly every single flower resulting in a pod. The plants are highly resistant to common bean diseases like powdery mildew and mosaic virus and, for me, produce two to three big flushes of beans throughout the summer.

The beans themselves are plump, juicy, around five inches long, and suitable for all purposes in the kitchen. We ate them fresh during the summer in soups and mixed vegetable roasts.

To preserve them, I freeze them in vacuum-sealed bags. Freezing beans is easy: Trim the ends of each bean, then throw them all at once in boiling water. The water will cease boiling due to the drop in temperature from adding the beans. As soon as the water starts to boil again, dump the beans in ice water. Once cooled, take the beans out and allow them to dry on towels or paper towels. Once dry, seal them in freezer bags and stick them in the freezer!

I feed these beans to my dog, too, and use them fresh during the summer but make sure to freeze plenty so I have them for the rest of the year as well.

Compass Bush Beans

Compass was a new variety for me (and the wider seed market) in 2024. We decided to grow this along with Provider because we were looking for a more tender filet bean to eat sautéed with our meals. Compass caught my eye because it was advertised as a very “upright” plant with easy-to-harvest pods. Provider bush beans are compact, but they tend to sprawl and can become a bit untidy. I hoped Compass might prove to have a neater growth habit while producing delicious filet-style green beans.

I was extremely impressed with this variety. Compass does grow very upright and is even more compact than Provider. The best part about this variety, though, is just how many beans each plant produces.

I don’t have a picture of the harvest (very sadly), but there was a day my husband and I spent hours picking beans and left the garden with my baskets overflowing. Provider beans made up a portion of the haul, but the vast majority were Compass. It seemed like, for each leaf on the plants, there were at least ten beans. It was a marvel the plants were able to remain standing under all that weight!

The beans are very uniform, incredibly tender, and have a wonderful flavor, making them perfect for eating as a side dish. Because each bean is thin, it takes quite a few pods to constitute a satisfying portion This isn’t anything outside the ordinary for a filet bean, but I do have one complaint against Compass.

While this variety was advertised as easy-to-harvest, I found that it wasn’t—at least for me. If you try to pull the beans off without clippers, they’ll tear apart. If anything, this shows just how tender they are, but it did make harvesting a bit tedious.

Overall, I was so pleased with my bean harvest this year. I didn’t struggle with any disease or pest issues and loved both of the varieties I grew. So, I’m going to stick with these varieties for at least another year.

Next year, I’m interested in trying some pole bean varieties, especially because I want to start growing dry beans to store! I don’t have the space for it this year, but might in 2026.

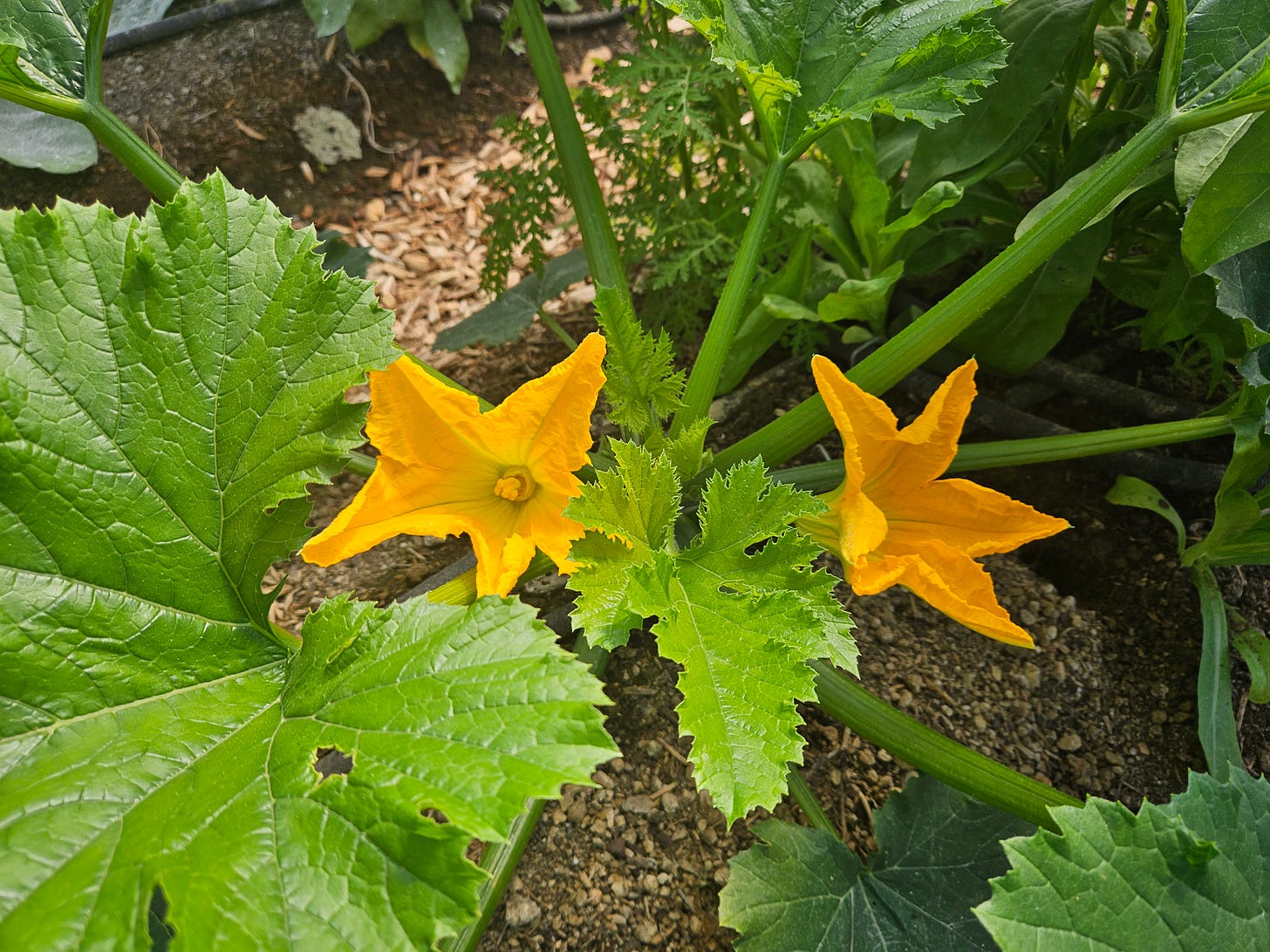

Summer Squash (Cucurbita pepo)

Summer squashes are heavy producers that grow best in hot summer temperatures. You can start them inside and transplant them, but I never do. Since they grow so rapidly and mature in only around fifty days, the advantage in giving them a week or two head start isn’t worth subjecting them to potential transplant shock. Instead, I wait until well after my last frost date, when the air temperatures are consistently above sixty degrees, and direct sow a few seeds in each of the places I want a plant.

This year, I intercropped my summer squashes with beans. I wanted to ensure the squash plants had plenty of room to stretch out, but since they wouldn’t sprawl right away, I sowed beans in the gaps. As the squash vines began to spread, I removed the bean plants that were in their way. I wasn’t sure how it would turn out, but I ended up with a great bean harvest and was able to leave several bean plants growing between the squash vines all summer.

I've found that squashes, in general, grow toward the sun. Their vines always tend to trail to the south. My hoop house runs east to west, so I had some problems with my squashes attempting to escape the hoop house through the southern side opening. I gently coaxed them to grow along the row using stakes, but they pretty much had their way in the end.

In July, I started to notice the tell tale signs of a particular pest on each of my summer squash plants. They kept putting on new fruit, but over time the squashes got smaller and decreased in quality. After two weeks, each plant had all but succumbed to the infestation so I decided to remove them from the garden early. In the end, I was really happy with how much summer squash I got from my three plants, but I needed to learn a valuable lesson about growing this crop.

Before we get to that, let’s look at both varieties.

In 2023, my zucchini plants were taken out by powdery mildew. So, I selected this variety to grow in 2024 because of its powdery mildew resistance. I also like that its growth habit is more bushy and less of a vine. This gives me more options when deciding where to plant it. Mine only grew to about five feet long but never seemed cramped. The leaf architecture is nice and open for such a truncated vine.

Desert is aptly named due to its drought tolerance and capacity to thrive in extremely hot temperatures. While mine weren’t subjected to drought, it was an abnormally hot summer. My yellow straightneck squashes would wilt during the day (which you can see in one of the photos above), but the Desert zucchini didn’t show any signs of stress.

I wanted to grow two of the Desert zucchini plants, but one of the seedlings I selected while thinning was a sort of genetic goof. It grew a few leaves and one flower but failed to produce a meristem (growing tip). So, after giving me a leaf and a flower it just remained as it was. I got rid of it.

Regardless, I was happy with the amount of zucchini I got off of just one plant. It wasn’t as much as I hoped for, but I was still able to enjoy grilled zucchini spears and make tons of zucchini bread.

Smooth Operator Summer Squash

As with the selection of Desert for my zucchini plants, this yellow straightneck squash variety, Smooth Operator, was also selected primarily for its high powdery mildew resistance. The plants have an open bush growth habit, too, like Desert, and their squashes are spineless which provides a pain-free picking experience (so long as you avoid the spines on the petioles).

This is one of the most productive summer squash varieties I have ever grown. At one point I was searching online for “ways to use a lot of summer squash at once.” I grew two of these plants and was able to pick around four squash every other day. As soon as we ate what was in the fridge, it was full again.

They are particularly delicious when picked early because they will rapidly develop a hard and unappetizing skin if left on the vine for even a day or two too long. So, I made it a practice to go out to check for new squash every day and erred on the side of picking them too early.

With an abundance of yellow squash, we got creative with how we ate them. We found this casserole recipe that is awesome as a side dish with fried chicken. I also made this summer squash soup recipe and froze several quarts of it that we are really enjoying during these cold winter months.

Mistakes

In 2023, my entire garden struggled with fungal and bacterial disease pressure. As I mentioned above, my zucchini plants were taken out of commission that year due to powdery mildew—a fungal disease. That motivated me to find methods of dealing with the heavy disease pressure in addition to selecting disease resistant varieties for 2024.

The good news is that none of my plants were infected with fungal or bacterial diseases in 2024. The bad news is that I didn’t adequately prepare for any other pests.

I’ve nicknamed 2023 as “the disease year” and have nicknamed 2024 as “the bug year.” In 2024, the bugs (and rabbits) discovered and populated my garden. For the summer squashes, the particular bug nuisance that led to their demise was the squash vine borer (SVB).

Dealing with the Squash Vine Borer

I wasn’t aware of the SVB’s existence prior to this year, and I had no reason to be. Before 2023, I wasn’t gardening in the mid-Atlantic where the SVB is present. I was gardening in the mountain west. It turns out, there are no SVBs there!

SVBs are moths that lay tiny reddish brown eggs on the petioles of squash plants. When the eggs hatch, the larvae eat their way through the leaf petiole and into the main stem of the plant. After enough time, or if there are enough SVB larvae present, the inside of the squash’s main stem gets eaten and hollowed out. The plant will not be able to transport water effectively and typically wilts, then dies.

SVBs will attack any cucurbit (pumpkins, cucumbers, melons, gourds, etc.) but they highly prefer Cucurbita pepo and Cucurbita maxima over Cucurbita moschata. C. pepo and C. maxima include most classically orange pumpkins and summer squashes like zucchini and yellow squash.

I was surprised to find my zucchini and yellow squash plants barely hanging on by a thread (literally) when I inspected them closely in mid-July, trying to find out why they were struggling. I noticed the sign of the SVB’s presence—insect frass that looks similar to sawdust—and went inside to identify what it was I was seeing. Upon finding out it was the SVB, I pulled the plants out of the garden and extracted every larva I could find from every plant infested with them.

I was worried that, if I just composted the plants, that the SVB larvae would continue eating and eventually pupate. I didn’t want them to have any chance of surviving so I went through the painful process of hunting them down, one-by-one. I used a sharp knife to cut open the squash stems and a pair of tweezers to pull the larvae out. To guarantee their downfall, I fed them to the chickens.

Dealing with the SVBs every year will be a big challenge. However, I have a few strategies that I’m confident will eliminate most of the threat.

First, I intend to do two sowings of summer squash. One in early Spring (~May 5th) and one in mid-summer (~July 15th). The sowing in May will mature and produce fruit before the SVBs emerge in force. However, I expect them to become infested and will cut them out of the garden at the end of June.

For the second sowing, it will be timed so that the plants germinate toward the end of the SVB period. I will cover the plants with pest fabric until they produce female flowers. At that point, it should be well into August, and the SVB pressure should be significantly diminished, so I’ll remove the pest fabric to allow those flowers to be pollinated.

Second, I am going to plant a trap crop of Blue Hubbard squash. Blue Hubbards are, apparently, the SVBs favorite treat. Since I know I’ll have SVBs every year no matter what I do, I might as well draw them to a crop I don’t care about. Toward the end of July, once the moths have laid all their eggs in the Blue Hubbard vines, I will destroy them using a lawn mower or burn them.

Finally, and most importantly, I intend to grow at least one variety of summer squash that isn’t a C. pepo, but rather a variety of C. moschata that the SVBs don’t like!

Next Year’s Varieties

The variety of C. moschata I chose to SVB-proof at least a portion of my summer squash crop is Zucchino Rampicante, a.k.a. trombone squash. While it isn’t resistant to disease, the vines are much thinner than those of any C. pepo variety, which makes it difficult for the SVB larvae to crawl through. Plus, it’s a climbing vine so I can either let it sprawl on the ground or grow it up a trellis to save room, a versatility I appreciate.

A bonus of growing Zucchino Rampicante is that it can be eaten fresh, but it also doubles as a winter squash! Allowed to mature fully on the vine, it will develop a hard rind that makes it suitable for long storage.

I’ll be growing Desert and Smooth Operator again in 2025, but I’m also adding a quirky new squash variety to the garden. It’s called Zapallito Del Tronco and it produces squash with edible rinds and creamy, buttery soft flesh that is akin to avocado. It belongs to C. maxima, so it will be attractive to the SVB, however I will only be sowing it during the second sowing in July and will be covering it with pest fabric while the plant is immature.

I am excited to add these new varieties to my garden and see how well I do in the battle against the bugs!

Up Next

No matter which varieties you grow, summer squashes and green beans are two highly rewarding crops. They produce heavily, don’t require much maintenance, and are versatile in the kitchen—whether you’re freezing beans for winter meals or finding creative ways to use an overflow of squash.

This past season taught me a lot, especially about dealing with pests like the squash vine borer. While it was frustrating to lose my squash plants earlier than expected, it motivated me to experiment with new varieties and strategies that I’m excited to test in 2025. Gardening is a constant cycle of learning, adjusting, and trying again, and that’s what makes it so rewarding.

I hope sharing my experience helps you in your garden, whether you’re trying bush beans for the first time or planning how to outsmart the squash vine borer. But I want to hear from you, too: Have you grown any of these varieties? What pests have you recently learned to manage? And who do you pawn your extra squash off on? Leave your thoughts in the comments below!

In the next installment—third to last in this series—I’ll be reviewing my garden fruit: strawberries and watermelon. 2024 was an incredibly enlightening year for growing fruit, so you won’t want to miss it.